With part 3 of this series, Evan Knappenberger’s and my discussion on shame and the mixed blessing, as presented in Ezekiel 36, concludes. In this essay, Evan traces the evolution over time of shame’s appearance within the Hebrews’ culture, thus providing a scholarly context for the stark dichotomy between the rationales behind shame, either worldly or heavenly, that were identified in part 2. Following Evan’s essay, I briefly respond to his contribution and bring this series to a conclusion.

Evan wrote:

Now I am fully submerged in this interpretive question of Ezekiel 36, a state of intellectual engagement with the text which is the natural end result of serious reflection upon the spirit of the text. Too long and too detailed for meeting for worship, our commitment to this iterative message between sister Patricia and I nevertheless requires more of us. It is becoming easy for me to see how some Orthodox Jews believe it is necessary to devote all their time and energy to studying and interpreting the scriptures. Without writing a whole treatise on the issue, however, I will try to once more to forge an association or two between our contemporary Quaker practice and the inspired words of one who, long ago, was given a message to proclaim to the empty wastelands of Judea (Eze. 36:1-6).

Central to our discussion is a distinction between shame and sin. A brief perusal of scholarly literature on the topic of shame in the Old Testament is enough to convince me of its centrality to the exilic context. Several perspectives emerge in the scholarly work, not least of which is the Honor-Shame paradigm, an almost universal thinking which shapes the ancient semitic understanding in a unique way. In this system, shame has many roles and serves sociality as a mechanism of control; it is contrasted with honor, both of which enable a certain attributional thinking among human beings. Honor and shame form a dyad whereby either is susceptible to idolatry, both in ancient and in the modern contexts — witness “honor killings” of disobedient daughters in some cultures. This interpretation of shame is helpful to contextualizing our passage in Ezekiel, as well as many other places in the Old Testament, especially in the Psalms. However, despite the fact that there are more than three dozen Hebraic words centering shame, it is something distinct (if not altogether different from) the concept of Sin. More importantly, Ezekiel clearly complicates post-exilic ideas of shame and sin — in chapter 36 alone, there are about three different approaches to the same idea.

Again, this is not the place to derive a study of the differences between Sin and Shame, though one of the best sources on this I have seen is purely historical (not theological.) Kyle Harper’s From Sin to Shame, (2013), details the fascinating cultural shift in the Roman world wrought by Pauline Christianity. According to Harper, early Christian notions of sinfulness were almost totally focused on sexual sin, and operated in a way that tended to appropriate and contrast pagan sexual ethics with the Christian concern for mutuality, respect, and love-of-neighbor-as-self. The notional development of Christian sexual ethics of course parallel not just Judaic notions of shame and sin, but worldly forces of honor and shame as well. As Quakers we are doubly aware of notional shame, which is written into the very appellation “Quaker.”

As a historian I am trained to seek the “forces of endogenous historical transformation” — those seeds of change which are planted in the psychic soil of any given place and time, which grow and bear fruit and often transform society in unexpected ways. It is easy in our case to see an axial transformation of shame in several stages: a primitive semitic honor-shame evolves with the Hebraic cultus into notional Sin, something more attributional which can only be cleansed by blood sacrifice; this further evolves in the post-exilic period into a systematized transactional atonement whereby Mount Zion is covered in a never-ending gore of blood that is alien to the prophetic conscience. (Here we are tempted to enter into the great contemporary debate on atonement on the side of James Alison and Ted Grimsrud, who emphasize the prophetic denial of sacrificial atonement which plays out in both Old and New Testaments.) Finally, the “seeds of endogenous transformation” come to fruition in a transcendence of sacrifice through the transformational death of Jesus on the Cross, his deconstructive wearing of our shame or “bearing of our sin” — and lastly in the late-Pauline doctrinal apologetics of the Epistle to the Hebrews.

In the first iteration, the Hebrew peoples formalize semitic shame, which crystallizes into Sin. The prophetic awareness maintains a minor interpretation of both shame and sin which foretells their negation through the transformative act of the Lord. (Witness, that in the Genesis 2 account of the Fall of Humanity, there is no mention of Sin, original or otherwise; only of the shame of nakedness.) While in exile, new generations of Israelites begin to understand shame and sin in a complex series of ritualized ethnic and social constructions which cannot resist oversimplification. The prophets, including Ezekiel, maintain their minor theology, even through the exile. By the time of the second temple and of Jesus of Nazareth, the ascendency of transactional shame and attributional Sin is complete. Jesus comes to a humanity almost entirely entrenched in its understanding of Sin, its reliance on the Letter of the Law which is death, and its ritualized reliance on death and shame upon which it builds a world order.

All of this is context for our interpretation of Ezekiel 36, with its insistent mixed blessing (which I lately realize is foreshadowed by Jacob’s lower back trouble marking him as blessed.) And it all points to Jesus’ embracing/deconstruction of shame and sin by which the foolishness of the wise is laid bare. It shows us a way to maintain our own minor interpretative theological awarenesses in the face of Anselmian sacrifice-Atonement and other like imperial constructions. Finally, it is for us Conservative Friends to uphold a prophetic ministry which opposes both worldly shamefulness and churchly Sin. May we continue to read scriptures like this deeply and enrich ourselves in them and the Lord.

Evan

Patricia wrote:

Thanks, Evan, for providing a scholarly outline of the evolving demeanor of “shame” among the Israelites. Chapter 36 in Ezekiel puts the dichotomous opposition of sin and faith before us when the prophet replaces the false cause of shame—heathenish reproach—with the true, sole cause of shame: alienation from God, i.e. sin. The chapter becomes relevant to present-day readers when we realize that the “heathenish reproach” can stand for all the worldly catalysts of shame, including religious institutions, ordinances, mores, and values. It is important to identify and know “the one thing needful” that keeps us from sin, for should Christ be known and heeded, all false measures that would induce shame go by the wayside.

Let’s conclude this discussion on Ezekiel 36 and look forward to future examinations of our faith through the wonderful resources offered within our Quaker tradition.

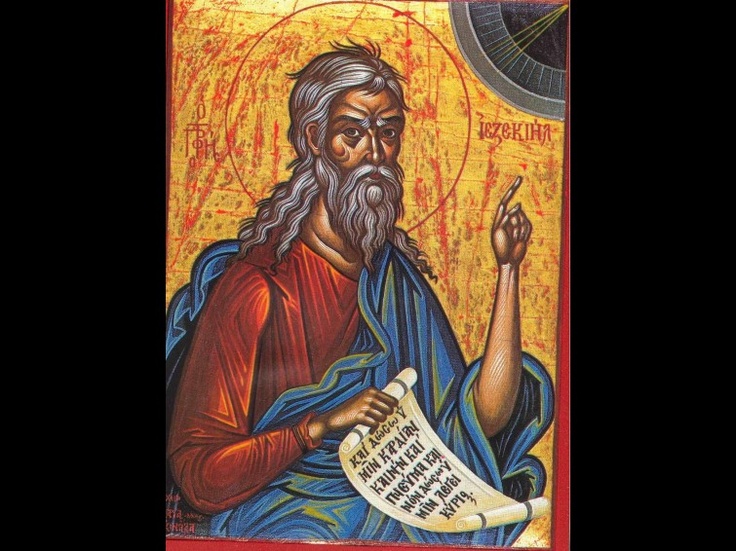

The Prophet Ezekiel Writing, 1465, Medieval manuscript in National Library Netherlands