At the festival season it was the Governor’s custom to release one prisoner chosen by the people. There was then in custody a man of some notoriety, called Jesus Bar-Abbas. When they were assembled Pilate said to them, ‘Which would you like me to release to you––Jesus Bar-Abbas, or Jesus called Messiah?’ For he knew that it was out of malice that they had brought Jesus before him (Matt 27:15–18 [NEB]).

In the New English Bible version of Matthew’s Gospel, “Jesus” is given as Barabbas’s first name. In Aramaic, his last name, “Bar-Abbas,” means “son of the father.”[1] In this story, only one Jesus, son of the father, will be chosen to live. It is likewise true that in each of our own lives, we, also, must choose one of the two spirits that are respectively embodied in these men. Whom will we choose: the spirit of Barabbas or the spirit of Christ? Which of the two spirits will animate and guide our life? Which of the two will have free rein in the heart? Which spirit—each with the same name and claim to entitlement—will live within? Will it be the one the world (the crowd) chooses, or will it be the one who must first die to the world?

Who is Barabbas?

All four Gospels mention Barabbas, but their descriptions vary: Matthew tells us that he was a “man of some notoriety”; Mark and Luke refer to him as a rebel and a murderer; and John calls him “a bandit.”[2] How we view Barabbas––freedom fighter or robber––does not alter the fact that his was a life engaged in the exercise of worldly power.

To be under the thrall of a foreign nation or to crave wealth settles as a wound on a person’s pride and leaves him with a weakened sense of himself. Against suffering the untenable state of a diminished self-image, Barabbas rebelled, and in attacking his fellow beings, he attempted to regain that self-regard. By overpowering others, taking their lives, property, or political authority, he could see himself as strong, i.e., as comparatively stronger. That this malicious dynamic is true wherever the worldly sensibility resides is confirmed not only by experience—historical, political, and personal—but also in the anchoring verse of this passage, spoken of one who is worldly and more crafty than noble: “For he [Pilate] knew that it was out of malice that they had brought Jesus before him” (18).

Barabbas’s true oppressor was not the Roman Empire nor his own lust for wealth; that oppressor was, in fact, his own fear of facing the truth of his existential condition, his fundamental inability to make life tolerable for himself. This universal human problem can be temporarily relieved by the acquisition and exercise of power, especially power over others. It is eternally relieved, however, only by means of courageously sustaining a regard for truth, though it leads to an impassable chasm where we teeter on the brink, stare into darkened depths, and faithfully endure in cross-like intensity.

“Do you refuse to speak to me?” said Pilate. Surely you know that I have authority to release you, and I have authority to crucify you?’ “You would have no authority at all over me, Jesus replied, if it had not been granted you from above” (John 19:10–11a).

For the word “authority,” substitute the word “power” in this exchange between Pilate and Jesus, and we have the quintessential showdown between the worldly and the heavenly sensibilities. It is the heavenly that has the final word, the final power: it is not the spirit of Pilate nor of Barabbas. Regardless of their differing worldly status, each had the worldly spirit: rebelling against and robbing both God and himself of his true nature as son of God.

Conclusion

In a recent meeting for worship, a Friend spoke of a problem that may come with knowing the stories of Scripture: this knowledge of the Bible can lead to crediting ourselves with more wisdom than is warranted. The ministering Friend used the story of Barabbas and Jesus standing before Pilate and the Passover crowd as an example. It was easy, he said, to criticize the crowd for choosing Barabbas over Jesus as the prisoner to be released, as we already knew the story. He asked us to consider if it was our knowledge the Bible story that led us to think that the choice was obvious. If we had been in that Jerusalem crowd and not known the story, what choice would we have made; whom would we have chosen to go free?

We can find the answer in self-reflection. Do we attack when we feel our self-image has been besmirched by another? Is the acquisition and retention of authority/power the impetus for our life? Do we trust the Father of life and his power to sustain our sense of personal worth, our sense of life, regardless of outward circumstance? Do we choose Jesus, Son of the Father, to be released and live free within our soul?

[1] Rees, T. “Barabbas.” International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia 1:402.

[2] Descriptions are found in Matt 27:16; Mark 15:7; Luke 23:19; and John 18.40. I’ve used the New English Bible in this essay.

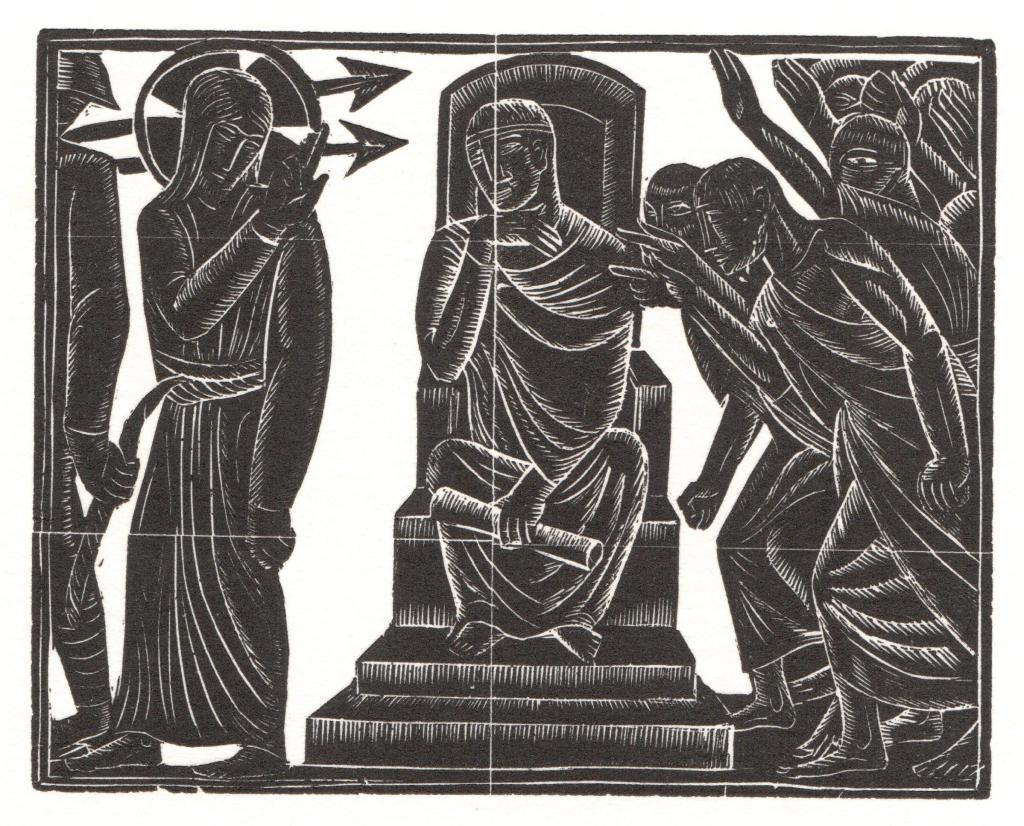

Jesus before Pilate, 1922. David Jones