The following is a transcript of an email discussion that took place in mid-July with Ryan Hodges, a Christian from British Colombia. This is the second part of a two-part post; the first part, presented last month, looked at the apparent discord between depictions of God’s Will in Old Testament stories and the character normally attributed to Him. Continuing with the same topic of God’s nature and intent, this second discussion centers on covenants.

Ryan’s July 17th email continues:

|

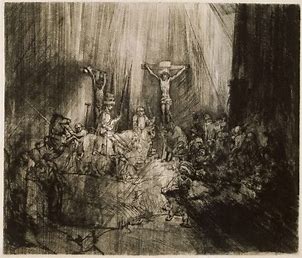

I am uncomfortable with the idea of “ministrations”, or as the rest of Christendom calls them: dispensations. This is what is always claimed about the genocidal stories of the Old Testament: “that was a different dispensation (ministration); God doesn’t deal with people in that way anymore. God wouldn’t ask us to commit genocide these days”. I cannot reconcile that idea with an unchanging God. This idea of dispensations (I believe) comes from a misunderstanding of the concept of a “New Covenant”. The idea of a new vs. old covenant was something that could be relevant to Jews in the time of Jesus/Paul, because they had actually lived under the Sinai covenant. Gentiles such as us were never under such a covenant. It seems nonsensical to me that Christians say, “we aren’t under the law anymore”, when we, nor our forefathers ever did live under such a law/old covenant. All we have ever had the option of, was the covenant as we have been offered through Jesus. How does “being under the law” mean anything to us gentiles? “New” in the Hebrew language holds the meaning of “fresh/vital” in it, it is not strictly and exclusively used as something that must be juxtaposed with something old. I think this is one of the jumping off points of getting into the whole “dispensations/ministrations” idea. It’s ok in a certain sense for Jews of Jesus day, to discuss the Old vs. New covenants, but for a gentile? I can’t see the sense in that. Patricia writes: You say you cannot reconcile the idea of different dispensations with “an unchanging God.” God doesn’t change his nature or intent; time, however, is the medium of change, and we, His creatures who inhabit time, manifest different/changing situations. God’s response to these situations will vary to the effect that His one unchanging intent is furthered and met: the kingdom of God on earth as it is in heaven. As for what does “being under the law” mean to us gentiles, I can think of a couple of things. First, in my Protestant religious training, the ten commandments were studied as God’s law, which we were to follow. Second, the idea of the authority of law is a hallmark of western civilization, and it can be traced back to the sacred authority allotted to God’s law as given to the Hebrews. Other societies had authoritarian strong men (such as Egypt’s Pharaoh) who ruled as they pleased with no authority (law) higher than themselves. This arrangement is typical not only of societies but also individuals where “the man of sin. . . sits in the temple of God, showing himself that he is God” (2 Thess. 2:3-4). Our civilization is one that recognizes the value of and is therefore regulated by law: international, national, state or province, and local. We all know what it means to be subject to law, and we get that principle from the Hebrews. So, when we get something new—something beyond the outward, socio-political law—to regulate our lives, we contrast the new way with the old way of obedience to the law. We know the old way of regulation – laws and principles – and when we are given the Christ, the living law in the heart, we know that this is the new and living way. The fresh/vital covenant is not something I see as initiated by Jesus, but he was a proponent of it. Adam had at least an opportunity to embrace it. Cain was counselled by God to embrace it. Enoch walked in it. Abraham found it “coming to the mountain on the third day”. Melchizedek seems to have been a priest in its ways. David wrote songs extolling its virtues. The prophets felt it, possibly walked in it, and encouraged others to embrace it. I don’t see this fresh/vital covenant as exclusively appearing after Jesus’ death and resurrection. Christ is the new covenant, meaning he mediates the relationship between God and His people. Jesus Christ is not a time-bound, worldly creature, such as is the unredeemed man who is the first Adam; Christ is the second Adam: not man but the Son of man; his life is not time-bound but is eternal. He asserts this difference when he says to the Jews: “Before Abraham was, I am” (Jn. 8:58). Yet, as a Galilean, he was also within time and ministering to the unredeemed, time-bound creatures around him that they might know God and Jesus Christ whom he has sent, which is eternal life (17:3). In his time-bound (historical) existence, he exemplifies our being which can (like his own) transcend our captivity within time (and thus subjection to death) and enter into the freedom of the eternal, while we yet are on earth. Hebrew prophets knew of this being who would appear in time and mediate between the natural, time-bound nature and the eternal; yet although they had borne witness to the Light, they were not that Light (Jn.1:7-9, Deut.18:15). They had not claimed that they and the Father were one, nor that we could be one with the Father as he was one with the Father (Jn. 17:21). We, too, are one with the Father through Christ, our mediator, just as two parties in a covenant figuratively become one. What was Jesus, while walking on this earth in the flesh, encouraging people to embrace in that “here and now” 2000 years ago? When he says in John: John 5:24 Truly, truly, I say to you, whoever hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life. He does not come into judgment, but has passed from death to life. He doesn’t say they “will have” eternal life. He says they do have it, he doesn’t say they “will not” come into judgement, but that they “do not” come into judgement, he doesn’t say they “will pass” from death into life, but that they “have passed” from death into life. He didn’t say these things as impending promises to be ratified after his death and resurrection and coming in spirit, he speaks of these things as present realities at the moment he spoke them. Why is this? As I understand it, it is because the “new” in the “new covenant” should not be understood as “new vs. old” but it should be understood as “fresh/vital”. He also states: “All who have learned from God, come to me.” And “If you had known God you would have known me.” Do we put the cart in front of the horse in saying we must know Jesus in order to know God? Isn’t Jesus’ point this: All who know what God is like will recognize me as coming from that God that they have already come to have known in some way? This “coming to have known God in some way”, I see has only taken place through the power of God’s ultimate covenant, his speaking directly to the heart of the individual. I agree that “that which may be known of God is manifest in [us] for God hath shewed it unto [us]” (Rom. 1:19) and think the same idea is present in John 6:44: “No man can come to me, except the Father which hath sent me draw him: and I will raise him up at the last day.” The thing that is often left out of these Old/New covenant discussions is the covenant that God made with Abraham, the covenant “of the pieces” in Genesis 15, this is God’s covenant of promise to Abraham in which he blesses Abraham’s descendants. This is the covenant promise that Paul speaks of, and of which Paul states that the “law” coming in 430 years later, cannot annul. In this sense the Sinai “covenant” is not truly the “first covenant” and it is not the covenant of God that he holds with the “faithful”. The law is not of faith, those who followed the law were to have life in keeping the commandments of that law, but that in no way abrogates the earlier covenant of promise made to Abraham and his “faith descendants”. Faith was a concept clarified in the life of Abraham, so he was the model of faith for those who would come after him, that does not mean that God’s covenant with those of faith did not exist before that time. I think Enoch is a perfect example of this “faith/new/fresh/vital covenant”. He walked with God, that’s it, that is all we know. And through walking with God, “he was not, for God took him.” Is this not what we are talking about when we talk about the cross? “losing your life to find it”? “taking up your cross and following”? Is this not the beating heart of the New Covenant as Jesus taught it? In the end I will mention that the Concept of the New Covenant as is understood by Catholics, Protestants, and Quakers alike, is strongly influenced by the “letter to the Hebrews”, and that this letter has a long history of being of questionable reliability in church history. “should it be included in the cannon?”, “are the concepts included in it worthy of the greater vision of scriptures?” That isn’t to say that there are not worthy ideas in it, but I believe that if it preaches a unique idea that is difficult to fit with the rest of the scriptures, that unique idea should be held under close scrutiny. Let’s work on the question about Hebrews another time. What Jeremiah identifies as the new covenant to come is the Lord’s putting his law in the inward parts, and writing it in their hearts (31:33). It is a relationship that is characterized by subjection to the Lord our Righteousness. Some willingly subject themselves to the inwardly known right and true, such as Abraham and other prophets (and those who hunger and thirst after righteousness [Mt.5:6]), and thus heed the drawings of the holy Spirit (Jn. 6:44); most do not. In John 21:20, the beloved disciple, John, is shown to have sought out the truth of his inward state, and thereby had subjected himself to the truth in the inward parts; whereas Peter in this chapter is shown to have needed some discipline, and was reminded several times that his actions/character weren’t acceptable. (For more explanation of this comparison of John and Peter, see the next to the last segment (titled “Preparation for the Work of Restoration”) in my essay To Stand Still in the Light). When Jesus says “And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me” (Jn. 12:32), he is anticipating the effect his dying upon the cross will have upon humanity. The historical cross is an example of man’s obedience to God’s intent/command, even unto the death. Through example, Jesus models to unredeemed man the necessity of obedience to God, and thereby the necessity of crucifying the worldly, self-serving life. As a visible act in history, the cross teaches us by example in a way that words might not. Some – the prophets and seers of all ages and places – already have known the inward process, the dying to the self that precedes receiving faith. But Jesus wasn’t interested in just a few; the Father’s Will was that “all men” (Ibid.) be drawn unto Christ Jesus and into his kingdom. Therefore, obedience unto death, and resurrection to new life, was enacted, and thus, as a figure or type of the inward process, shows the way to all. These are very difficult ideas to express. I think the closer one keeps to the inward experience of what all the imagery and history portends, the more accurate one’s ideas can be. I hope my explanations have reached a place of understanding in you, as they may require as much effort on your part as they have on mine. |

I value and appreciate this discussion very much. Thank you both. Mickey E.

LikeLiked by 1 person