This past month my daughter sent me a podcast in which was recounted the life history of Benjamin Lay, an early abolitionist and Quaker of the 18th century. Lay often acted as would a modern performance artist, engaging in inventive acts for a political cause: he sought to shame slaveholding Quakers into an awareness of their cruelty and hypocrisy. Unsurprisingly, his performances were not well-received, and in 1738, he was disowned by Abington (Pa.) Meeting. Lay retreated from Quaker society to live in a cave not far from the meetinghouse, his abode furnished with a private library of two hundred books. Centuries have passed, and Lay, once deemed a gadfly, is now hailed a hero.

How does the sequence of Lay’s critique of and then retreat from society pertain to chapter 15 of the Gospel of Mark? In both instances, the light of the Word exposed the dark spirit, which, in turn, strove to overcome it by silencing the speaker through banishment or death. With the darkness exposed and his work done, the prophet in each case became silent, leaving the corrupted social body to itself: either to acknowledge the reality the light had revealed, or to refuse to see and to remain in darkness.1

In the several decades following the testimony of Benjamin Lay, the Society of Friends slowly moved toward accepting the reality that slaveholding is sin, and in 1776 (17 years after Lay’s death), Philadelphia Yearly Meeting deemed the owning of slaves to be an offense requiring disownment.

In Mark 15, which tells of Jesus’s crucifixion and death, we find the same pattern that regularly occurs when light has shone forth in darkness: there follows worldly persecution; prophetic silence; and ultimately, the world’s acknowledgment of truth. In this narrative, however, the sequence is greatly compressed in time: the apprehension of truth comes moments after Jesus’s death. First to speak, a centurion, seeing “how [Jesus] died . . . said, ‘Truly this man was a son of God’” (39). That this expression of convincement was uttered by one so greatly averse to the Way (being a supporter of empire as well as an executioner) portends the universal restoration of humanity to its true state of seeing and becoming sons of God.

Contagion (1-32)

Before reaching the centurion’s words, however, the chapter reviews the labyrinth of iniquity through which Jesus, silent and unresisting, is dragged. The first two-thirds of chapter 15 illustrate the spread of corruption and ignorance—up, down, and throughout the social hierarchy. Pilate, a Roman prefect (governor), wields imperial power and therefore is in society’s highest echelon; he is petitioned by the chief priests to treat Jesus as a criminal (1-3). At the other end of the social spectrum are the people, whom the priests stir up to cry out for Jesus’s crucifixion (11, 13-14). So tainted is the society with the dark, demonic spirit that nowhere can be found the pure light of truth, and Jesus is all but silent, knowing that this is the way of things.

His one statement throughout his captivity is in response to Pilate’s question: “Are you the king of the Jews?” Jesus doesn’t answer him directly yes or no (thereby denying the prefect’s power) but instead makes Pilate himself an unwitting exponent of truth when he answers: “The words are yours” (2).

Jesus’s refusal to speak in his own defense during the remainder of his ordeal implies his early statement to Pilate stands applicable to every opposition he encounters. His continuous silence drives home the fact that the violators’ words and actions are their own—their responsibility alone—and not his. He will not take part in, cooperate, nor assert himself (5); neither does he engage them nor accept their tender mercies (23), for to do so would give latitude to yet more self-deception in their already corrupted souls. If Jesus were to take part in the proceedings—even to resist—his participation would allow the persecutors to claim that he had brought upon himself the treatment he receives, and as such, that he should bear the burden for what is, in fact, their sin. Even Pilate can see that the responsibility for this travesty lies upon the chief priests and their malice (10).

This glimmer of insight shown by Pilate does not absolve him of corruption, only of ignorance. His interaction with the mob regarding Barabbas, the prisoner to be released (6-15), recalls the populist politician who can “whip up the crowd into a mob frenzy.”2 In his first receiving Jesus from the chief priests and then delivering him to the soldiers to be flogged and crucified (15), Pilate is the center link in the chain of crime. It is this “division of labor” that allows each party to deceive themselves into thinking they are absolved of responsibility for wrong-doing; thus Jesus’s arrest, trial, persecution, and death illustrates the most spiritually dangerous, destructive configuration of “the prince of this world”: collusion among the wicked.

Darkness over the whole land (33-37)

That Jesus is the “king of the Jews” is a motif woven throughout chapter 15. Early in the chapter in verse 2, Pilate asks Jesus directly: “Are you the king of the Jews?” Later before the crowd, Pilate uses the phrase to rile the mob (9, 12). For the soldiers, it provides opportunity to address Jesus mockingly (18), and as a criminal charge, it is inscribed above Jesus’s body on the cross (26). Finally, in a vile culmination of corruption and ignorance, the chief priests and scribes use the term “king of Israel” to mock Jesus as he dies:

Let the Messiah, the king of Israel, come down now from the cross. If we see that, we shall believe (32).3

This chapter has steadily, increasingly brought the darkness of moral and intellectual error to the fore. That is to say, corruption and ignorance have become acute. So severe does the darkness become that it envelopes the land, though the sun be at its zenith in “the sixth hour” (33). Lasting three hours (three, in Hebrew, being the number of completeness) “until the ninth hour,” we are being told that the darkness is at its greatest intensity. At this point, Jesus’s words come forth: “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” (34) Sensing abandonment, being forsaken by God, is to have lost sight and hope: the darkness is absolute.

That Jesus speaks these despairing words in Aramaic, his native tongue, rather than the Hebrew in which Psalm 22 (from which these words come) was written is interpreted in this way: individual, personal experience of the typology of Scripture is required of everyone. The Cross is personal and inward, as early Friends knew and preached.4

Though the corruption of the priests is no longer on view at this point in the narrative, the darkness of ignorance remains, and verse 36 gives us the chapter’s final expression of spiritual blindness as portrayed by the bystanders who mistake Jesus’s words for a call to Elijah: “Hark, he is calling Elijah. . . . Let us see . . . if Elijah will come to take him down” (35-36). With Jesus’s death (37), even the darkness of ignorance is overcome: following the rending of the temple veil that figuratively separated God and man, the centurion states: “Truly this man was a son of God” (39).

Outspreading (40-47)

First evidenced in the centurion, awareness of and right regard for Jesus grows steadily throughout the remainder of this chapter and into the next. The growth is first seen in numbers, as women—many women—who followed, ministered, or came with Jesus to Jerusalem look on, though they be far off, and thus their vision is but small. Yet watchful from a distance, the women see the Son of man, the master of the house (Mk.13:33-37).

Right regard for Jesus gains ground within the social hierarchy when next appears one who is individuated by name: Joseph of Arimathaea. As an individual and a male, Joseph not only stands in patriarchally favored contrast to the group of women, but more significantly, as an individual who is named, Joseph stands apart from the undifferentiated cackle of corrupt priests. The contrast between them and Joseph is further heightened by the fact that though both the priests and Joseph are peers in the Council (the Sanhedrin, which was the supreme court of the Jews), only Joseph is described as “a respected member of the Council” (43).

As a “respected” member of the highest court, Joseph is distinguished as having good judgment. In the same verse, we learn that he “waitedfor the kingdom of God” (43 KJV). That these two facts occur in the same verse suggests there is a correlation between good judgment and waiting to receive God’s kingdom.

Joseph understands that God and his kingdom must be waited for: that he himself is not a god, and therefore he does not exalt himself by claiming that he need not wait but perpetually inhabits the kingdom. In contrast, the priests (neither differentiated nor esteemed) see themselves “as gods knowing good and evil,” thus claiming for themselves a power of judgement that they do not have. The text implies that one must wait for and receive the virtue and power of God to judge righteously: to be enabled to distinguish good from evil, King from subject, and Christ from self. One must know the difference experientially before one can make a distinction intellectually (1 Cor. 6:2 KJV).

Joseph makes this distinction, and therefore he waits for the kingdom of God, thereby showing the good judgment for which he is respected. To reinforce the idea that Joseph’s waiting is the preparation needed to receive the kingdom, he appears on “Preparation-day (that is, the day before the Sabbath)” (42), which suggests that Joseph judiciously prepares for the Rest to come: he prepares and waits for the kingdom of God (43).

Second, we see that Joseph is not only a man of humility and good judgment but also a man of courage and one who takes responsibility: Joseph “bravely went in to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus” (43); he, at his own cost, then provides Jesus with a respectful burial (46). Joseph’s actions mirror in reverse those of the priests who delivered Jesus to Pilate (1) and treated him disrespectfully (32).

In verse 44, we see Pilate continue his policy of questioning others (2, 4, 9, 12, and 14) and letting their answers determine his actions: he thus equips himself at every turn with opportunity to deny personal responsibility. (And therein is he contrasted with Joseph.) In this passage, after questioning the centurion (44), Pilate—ever the middleman—releases the body to Joseph: the death effected as much by his lack of moral responsibility as by the priests’ and people’s villainy.

In the next and final chapter of the Gospel of Mark, we will see a continuation and acceleration of the forward momentum toward regard for and knowledge of Jesus as Lord. In this chapter, however, the story ends with the women standing by: women who are named, individuated; waiting; alert and watchful.

And Mary Magdala and Mary the mother of Joseph were watching and saw where he was laid (47).

1. “Here lies the test: the light has come into the world, but men preferred darkness to light because their deeds were evil” (Jn. 3:19). I’ve relied primarily on the New English Bible throughout this essay. When I’ve used the King James Version, I’ve so indicated in the text.

2. This quote is from Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin, taken from his book Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy .

3.The priests’ insistence upon Jesus meeting their skewed criterion of Messiahship is tantamount to their claiming themselves to be the arbiters of good and evil, that is, to “be as gods, knowing good and evil” (Gen. 3:5). This lie is the serpent’s temptation that led to humanity’s fall from grace. It is appropriate that this particular offense (which is echoed in the same verse by the thieves’ taunting) appears in the narrative at the point of greatest darkness, for it was the first sin in Eden and is shown to be the last at Golgotha: suggesting that—first and last—to exalt the limited, natural perspective is the root of all sin, the sin of pride. That the error issues from both the priests and the thieves tells us that whether high-up or low-down, all are guilty who presume to judge—to discern good from evil—while constrained by the fallen nature of the first Adam.

4. That the Cross must be borne by everyone is suggested by the figure of Simon the Cyrenian, an everyman passerby, who was required to carry the cross (21).

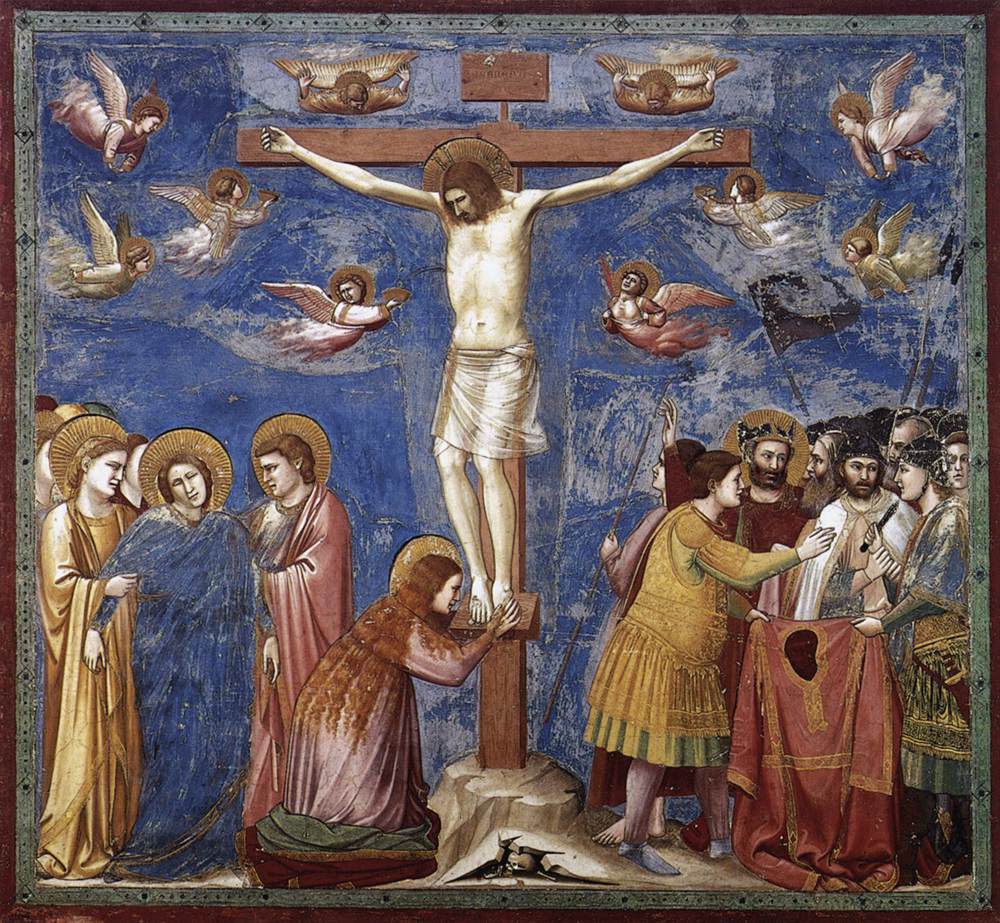

The Crucifixion, 1303-05, Giotto