And he said unto them, Verily I say unto you, That there be some of them that stand here, which shall not taste of death, till they have seen the kingdom of God come with power (Mk. 9:1).

In chapter 8, we saw Jesus accepting his new role as Messiah, which then allowed him to call others to the same self-denial or taking up of the cross to which he himself had acceded. One might think this first verse of chapter 9 would be better placed in the preceding chapter, as it continues the scene begun a few verses earlier in 8:34. Chapter 9, however, features Jesus preparing for his earthly departure by educating his disciples to the end that they and others might come to see the kingdom of God. Thus it is appropriate to have stated at the beginning of this chapter the intent of the work for which the disciples are being trained: that some may come to see “the kingdom of God come with power.”

This teaching chapter has two main lessons: 1) there is a new vision of life that is above and beyond worldly capacity to know, and 2) its ways and means are distinct from worldly ways and means, and are taught by the Son of God.

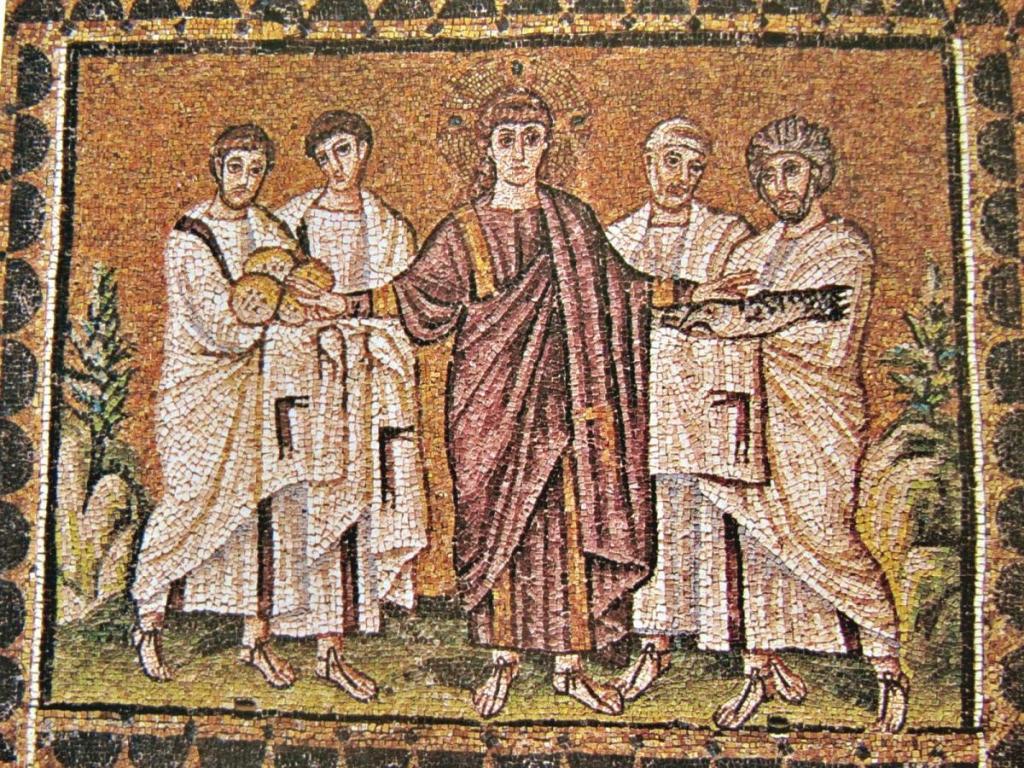

The Transfiguration

How better to impress upon the three leading disciples (Peter, James, and John) that there is a reality hitherto beyond their ken than to bring them into a new space, “an high mountain” (2), and before their eyes to be moved into that brilliant reality, which is the Light! That this phenomenon is legitimately grounded in the tradition is affirmed by the appearance of Moses (the Law) and Elias (the Prophets). The disciples are desirous to normalize the event by building tabernacles, yet they are prevented from doing so. That is to say, they are prevented from taking an active hand in worship – worshiping in man’s will – and are instead instructed by God to worship in the new way: by hearing the Light that is the Son of God (7). Having witnessed the transfiguration from flesh to Light is the first and necessary lesson for these disciples, for until then only the darkness of worldly life had suffused their awareness. They had need to see, to experience the Light, for how could they bring others into the kingdom if they themselves did not know, had not seen, its reality.

In admonishing the disciples to “tell no man what things they had seen”(9), Jesus is taking steps to prevent speculation. It is essential that knowledge be gained in a manner more akin to sensory experience, i.e., hearing, seeing, tasting, rather than conjecture. For human pride often enthrones conjecture with a certainty that is not warranted, and thus usurps Truth’s rightful place.

It is conjecture about the meaning of “rising from the dead” that the three disciples engage in amongst themselves as they come down the mountain (10). That they then question Jesus about the prophet Elias tells of the tradition’s close association of Elias’s return – a prophet rising from the dead – with the subsequent coming of the Lord.1 Jesus identifies John the Baptist with Elias, in that the righteousness of which man is capable in and of himself was the necessary and core attribute of all prophets, and John exemplified this quality most fully. Ironically, in chapter 6, these several ideas of rising from the dead regarding Elias, John the Baptist, and Jesus are likewise linked by Herod, John’s executioner.2 In turn, Jesus obliquely links Elias, John, and Herod in the verse concluding this section: “But I say unto you, That Elias is indeed come, and they have done unto him whatsoever they listed as it is written of him” (13). That the messianic rising follows upon the prophetic diminishment is a motif presented repeatedly in this and the previous chapter where Jesus himself moved from one to the other: we are being told that the prophetic and the messianic are linked and similar but sufficiently distinct to have their difference noted repeatedly at various times and by disparate characters.

Thus in this first lesson Jesus gives to his disciples, the reality of the kingdom of God is shown in the transfiguration (2-3) where flesh becomes Light and the beloved Son is to be heard (7). Furthermore, the triumphant reign over inevitable worldly opposition is foreshadowed in the words “the Son of man were risen from the dead” (9). Having experienced the Light of Christ and having been taught the dynamics of opposition and triumph that are to be expected, the disciples are now ready to see a demonstration of the work they will do. They are to see humanity in its rebellion, its ignorance, pride, cruelty, helplessness, and grief, and they are to overcome it all.

The people and the authorities (14-16)

Increasingly, Jesus has become less willing to engage the authorities: in verse 16, he asks a question of them and does not stay to hear their answer. It would appear that his previous encounters with the authorities were predicated on weaning the people away from their influence. That is no longer necessary, as the people who have been speaking with the scribes quickly lose interest in them when Jesus appears (15). Diverting his attention from the scribes and moving on to those conscious of the need for help, Jesus models spiritual triage: for his disciples, a lesson in practicality. Time and resources are limited and must to be spent where most productive.

The healing (17-29)

Although this healing story features particular characters, a distraught father and his demon-possessed son, it serves, in fact, as a universal template for humanity’s unredeemed condition. In Scripture healing stories, a son or daughter – that which is most precious to us in our fleshly life – often functions as a symbol for the soul, that which is most precious to us in our spiritual life. That the son in this story is debilitated by a troubling spirit is to say that the human soul is troubled by a debilitating spirit. Upon hearing the father’s list of his son’s symptoms, Jesus immediately interjects the diagnosis: “O faithless generation”(19). Note his use of the word “generation”; he does not address the man directly but expands his particular problem to encompass many people: an indication that it is lack of faith that universally troubles and debilitates the human soul, the human life.

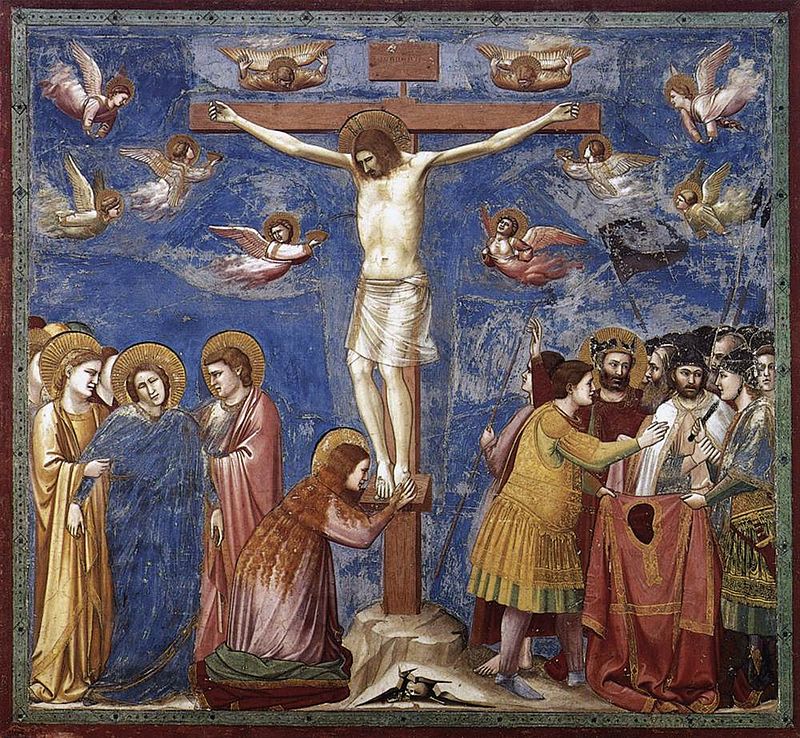

The father, brought to desperation in his fully exercised but inadequate power, cries out in tears from his earnest heart, “Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief” (24). All the elements for receiving faith are thus present: the recognition of the soul’s need, that all one’s earnest effort cannot meet that need, and the crying out for help. The Lord can then proceed to exorcise the demonic spirit from the soul and forever prevent its return (25). The son’s appearing dead at first but then lifted up to life (27) prefigures the resurrection to life that Jesus will model following his crucifixion and entombment, which he refers to a few verses later (31). His crucifixion, entombment, and resurrection, in turn, prefigures our inward, spiritual ascension to Life.

This healing episode is a lesson that provides a prototype for the work the disciples must come to do. We are reminded that it has been a lesson when they ask Jesus why they themselves could not cast out the demon (28). He replies, “This kind can come forth by nothing, but by prayer and fasting” (29). Fasting is the restriction of worldly appetite, and prayer is communion with God. Jesus is teaching his disciples that the demonic is cast out following the restriction of the worldly appetite and the ascension into heavenly communion.

How the disciples are to conduct themselves

Having shown the disciples the work they are to do in the world, Jesus then spends the remainder of this chapter on the inward discipline they are to maintain that they may perform this work, both individually and among themselves. Each disciple must consider his primary role to be serving others in their progress toward the kingdom (35); it is the kingdom that matters, not one’s position in the worldly hierarchy. To empathize with and assist the unworldly innocent is to integrate oneself into the way of Christ and God (37). Attend to the spirit a person manifests, not to the letter of his words (39-40). Those who provide relief to you (and you will need it!) shall be favored by God, and, conversely, for those who thwart the unworldly innocent, it were better for them to be without life altogether, for their souls are irrevocably sunk in the chaos of hell (42).

And if thy hand offend thee, cut it off: it is better for thee to enter into life maimed, than having two hands to go into hell, into the fire that never shall be quenched:

Where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched.

And if thy foot offend thee, cut it off: it is better for thee to enter halt into life, than having two feet to be cast in hell, into the fire that never shall be quenched:

Where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched.

And if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out: it is better for thee to enter into the kingdom of God with one eye, than having two eyes to be cast into hell fire:

Where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched (43-48).

This passage near the end of chapter 9 differs in style from what has come before, and through its poetry indelibly stresses the necessity of disallowing worldly inclinations from interfering with one’s determination to enter the kingdom. For if a person does not enter the kingdom himself, he hardly can expect to assist others in the same pursuit. What one does (the hand), where one goes (the foot), what one desires (the eye) are to be kept aligned and purposeful to the end that the kingdom is entered. Maintaining this intent is essential, and so Jesus uses repetition and refrain to impress upon his disciples the all-important oversight and regulation of their inward state.

For every one shall be salted with fire, and every sacrifice shall be salted with salt. Salt is good, but if the salt have lost his saltness, wherewith will ye season it (49-50)?

Beautiful is Jesus’s play upon the word “salt” in the final two verses of this chapter. Continuing with the reference to the “fire” of hell from the prior admonitory passage, he speaks of the difficulty of making the sacrifice of one’s worldly self (everyone is “salted with fire”) while also alluding to the tradition’s practice of the salting of temple sacrifices.3 “Salt is good”; it is the essential seasoning: just as a vital soul seasons all one’s being. Life loses its palatability when not seasoned with a soul that lives in the Light. Jesus completes this teaching chapter by calling his disciples to keep this necessary seasoning, the living soul, in themselves, for it is that which allows for “peace one with another” (50).

Throughout this teaching chapter, Jesus has provided experiential knowledge of the kingdom, a demonstration of the work to be done, and numerous guidelines for maintaining the vitality of spiritual life within and among his disciples.

1 “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the Lord” (Mal. 4:5). “Elijah” is the prophet’s name in the Hebrew language, while “Elias” is the Greek form.

2 And king Herod heard of him [Jesus] . . . and he said, That John the Baptist was risen from the dead, and therefore mighty works do shew forth themselves in him. Others said, That it is Elias. . . . But when Herod heard thereof, he said, It is John, whom I beheaded: he is risen from the dead (Mk. 6:14-16).

3 And every oblation of thy meat offering shalt thou season with salt; neither shalt thou suffer the salt of the covenant of thy God to be lacking from thy meat offering: with all thine offerings thou shalt offer salt (Lev. 2:13).

Transfiguration, 1442 Fra Angelico